How to Get Faster: The Missing Link in Max Sprint Speed

Most athletes never truly train max velocity. Learn how to get faster by improving top-end sprint speed with science-backed methods.

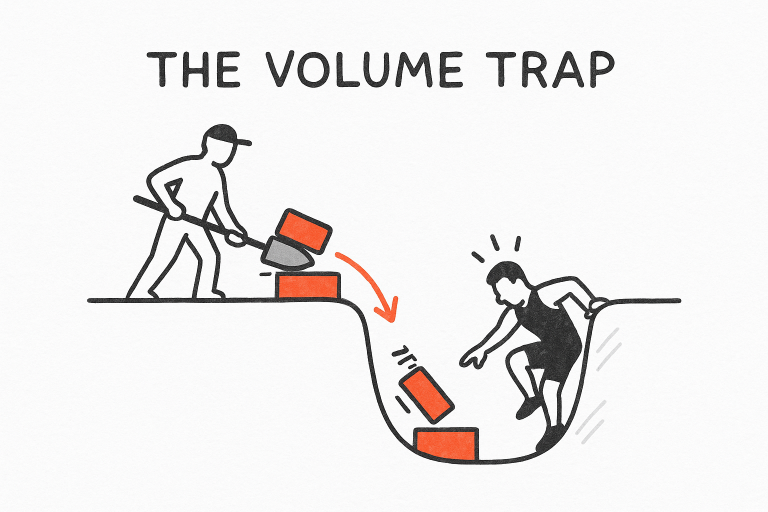

Every coach and athlete has seen it: the athlete who gives everything, trains longer, adds extra sets after practice — and somehow gets slower.

It’s a paradox: more effort, less progress.

This is The Volume Trap — the hole coaches dig with good intentions, athletes fall into with pride, and both struggle to escape.

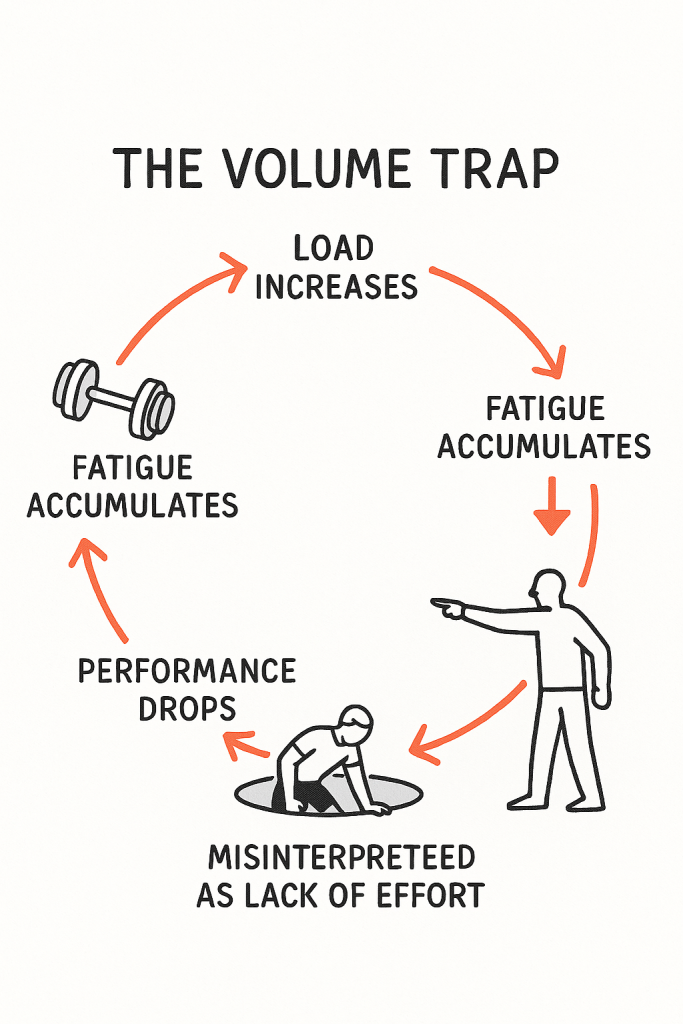

In most cases, the pattern looks like this:

Then comes the blame: “You’re not trying hard enough.”

But the real issue isn’t effort — it’s recovery.

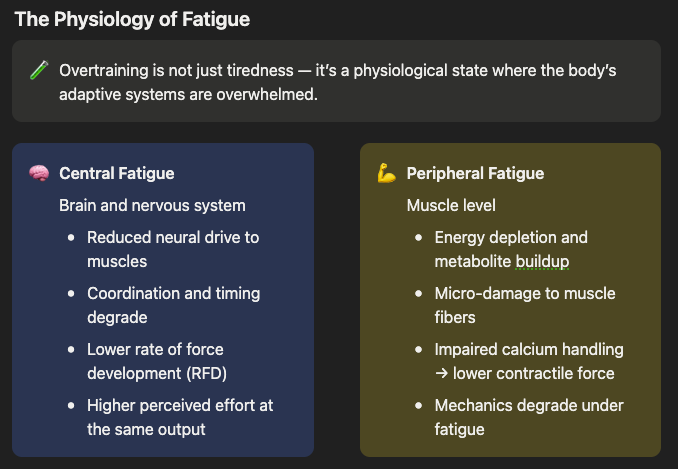

Overtraining is not just tiredness — it’s a physiological state where the body’s adaptive systems are overwhelmed.

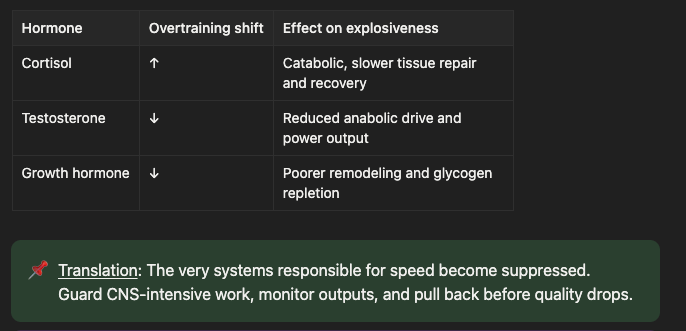

According to Meeusen et al. (2013), chronic overtraining alters hormone balance — increasing cortisol while reducing testosterone and growth hormone — which slows recovery and lowers readiness for explosive efforts.

Translation: The very systems responsible for speed become suppressed.

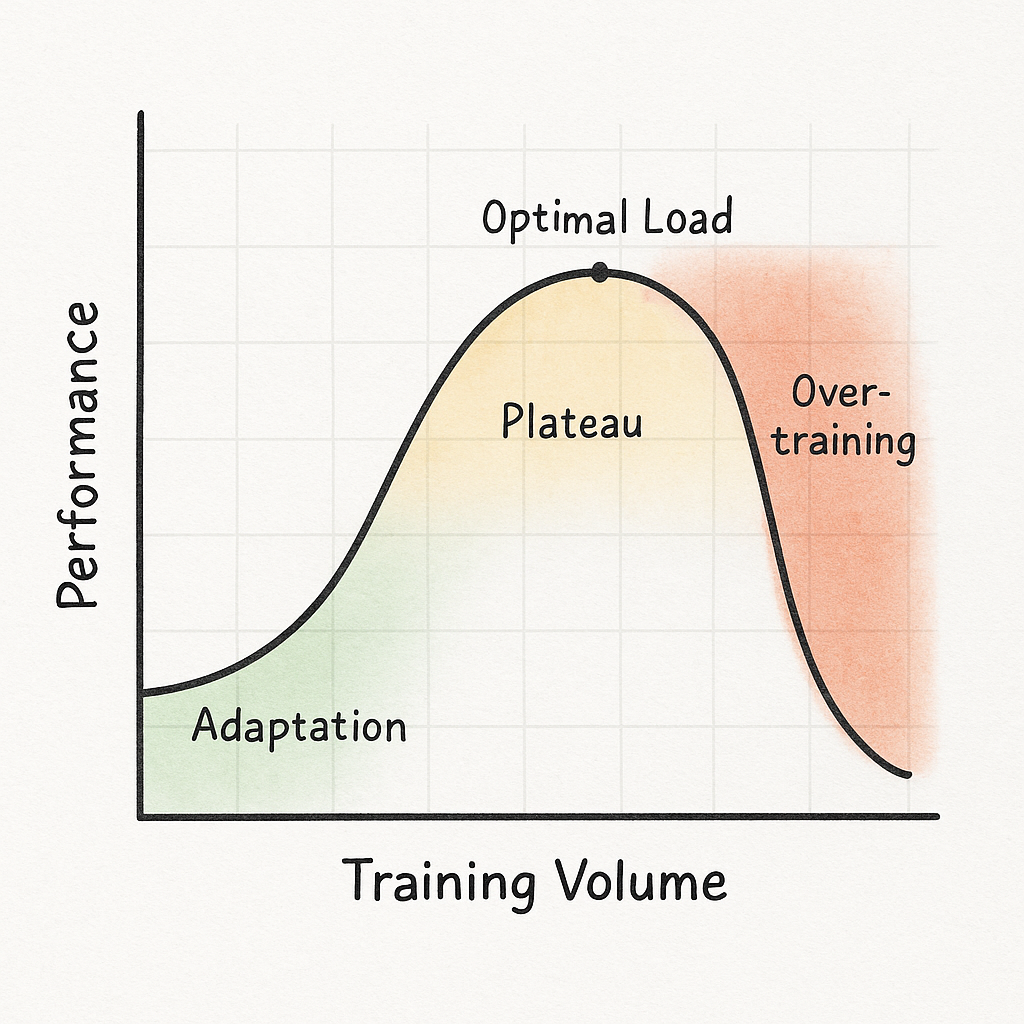

Training works by stressing the system just enough to trigger adaptation. This is called supercompensation:

Stress → Recovery → Adaptation → Performance gain.

But if recovery doesn’t keep up, the curve reverses. Instead of supercompensation, you get maladaptation — performance declines even as effort increases.

Supporting Data:

A 2020 Sports Medicine meta-analysis found that athletes under chronic load (>3 weeks of insufficient recovery) exhibited reduced maximal strength, lower jump height, and impaired sprint performance due to neuromuscular fatigue (Kiely, 2020).

In Sports Medicine, Smith (2003) noted that persistent overload decreases muscle contractility and coordination.

Budgett (1998) showed that overtrained athletes exhibit symptoms resembling illness: disturbed sleep, mood changes, and reduced appetite.

Mechanically, fatigue lengthens ground contact time and lowers vertical stiffness — both death sentences for sprinters.

What feels like “working hard” is really a slow erosion of the athlete’s elastic system.

Fatigue is deceptive — it feels like progress.

Coaches often equate exhaustion with work ethic. Athletes fear rest will make them soft. Both sides buy into the same illusion: more = better.

But neuroscience says otherwise. Chronic fatigue disrupts the prefrontal cortex’s ability to judge effort and output accurately (Noakes, 2012). The brain literally becomes worse at recognizing when the body needs rest.

Fatigue → Misinterpreted as Lack of Effort → Increased Volume → Performance Decline → More Fatigue.

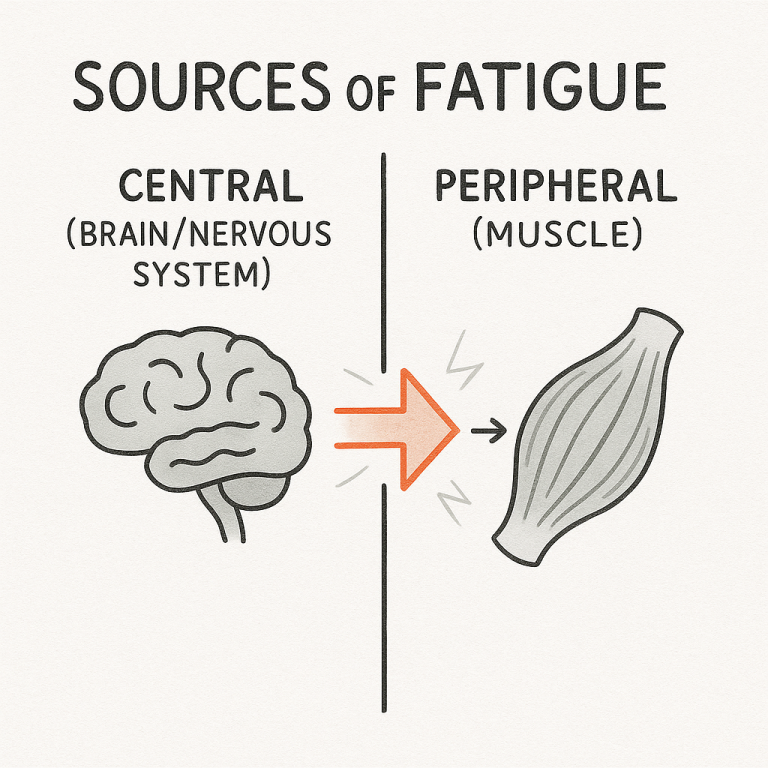

Sprinting depends on the ability to apply large forces quickly — high rate of force development (RFD). Overtraining reduces neural firing frequency and impairs synchronization of motor units.

Morin & Samozino (2018) demonstrated that when fatigue accumulates, athletes produce lower vertical stiffness and longer contact times, directly correlating with slower sprint velocities.

Excessive volume floods the system with metabolic byproducts (lactate, hydrogen ions) and reduces glycogen stores, impairing repeated high-speed efforts.

Nédélec et al. (2013) found that inadequate recovery lowers phosphocreatine resynthesis and elevates inflammation markers, prolonging fatigue for days.

For sprinters, that means loss of bounce — the reactive elastic quality that separates explosive athletes from tired ones.

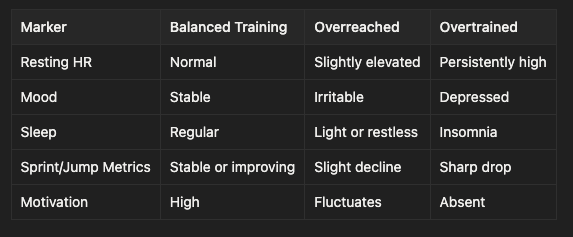

Overtraining sneaks in quietly. These evidence-based red flags signal the volume trap is closing:

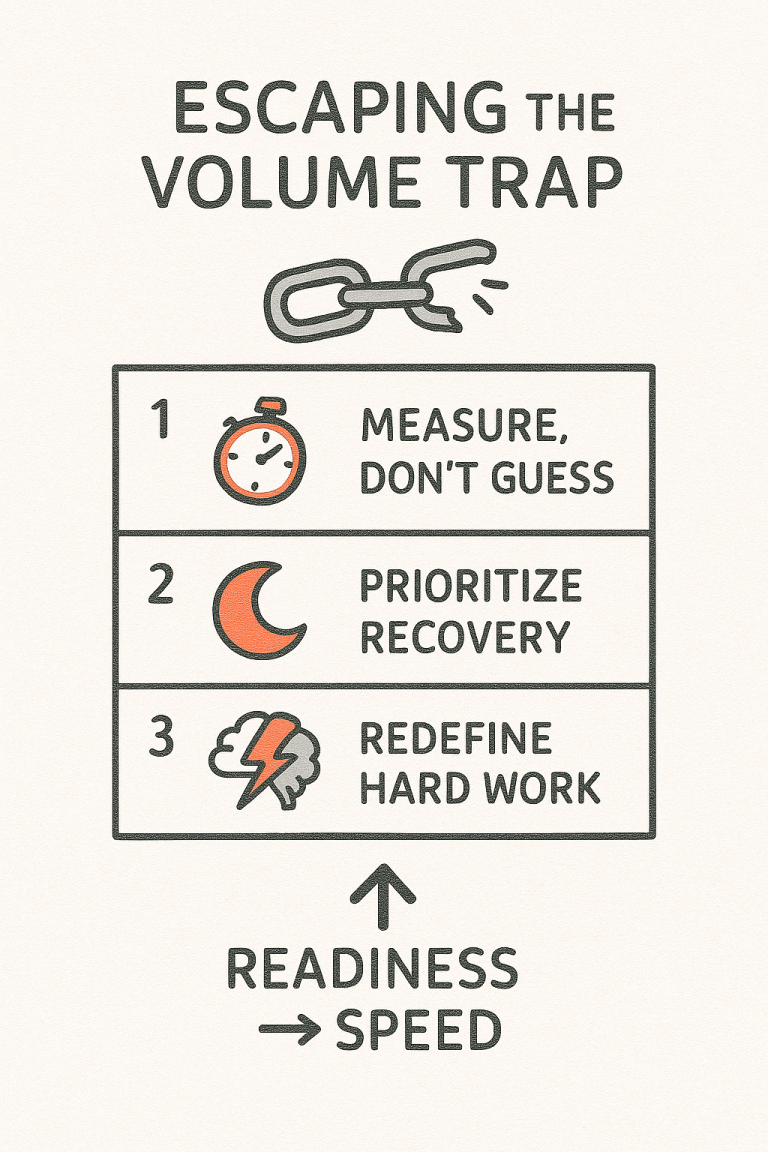

Subjective effort is unreliable — data isn’t.

Use tools to quantify readiness and fatigue:

Impellizzeri et al. (2005) emphasized that simple load monitoring (training volume × intensity) predicts performance trends better than subjective ratings alone.

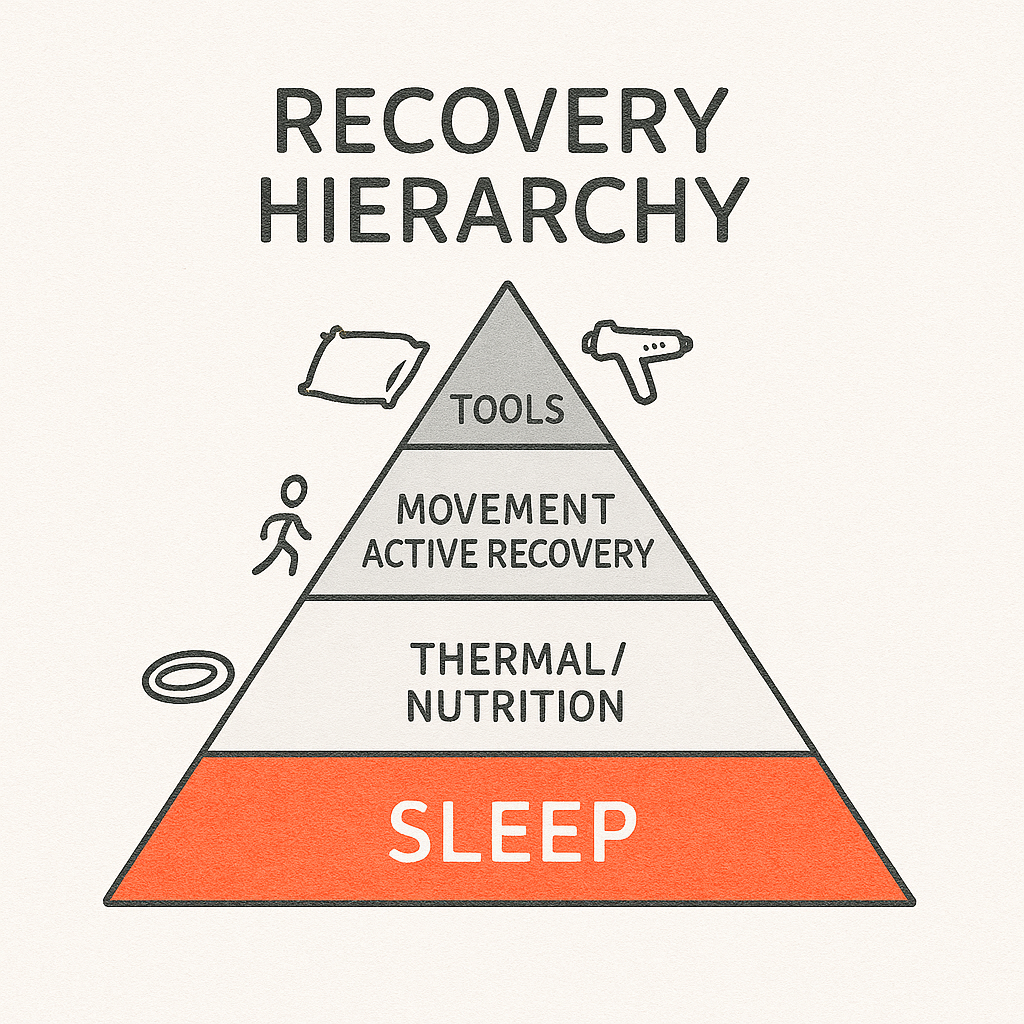

Recovery isn’t the absence of work — it’s the phase where adaptation happens.

Top programs treat recovery metrics like training metrics.

Evidence-backed recovery boosters:

(Nédélec et al., 2013, Sports Medicine)

Hard work isn’t about exhaustion — it’s about execution.

The best coaches know when to push and when to pull back.

You don’t train to get tired — you train to get faster.

Great programs leave athletes confident, not broken.

The Volume Trap is a feedback loop where overtraining masquerades as hard work.

Fatigue dulls performance, prompting even more volume — which digs the hole deeper.

Smart coaches manage load, monitor data, and respect recovery as the true driver of adaptation.

Because sometimes, the fastest way to get faster… is to stop doing so much.

Q1: How do I know if my athlete is overtrained or just tired?

Track recovery over time. If metrics and mood recover within 48–72 hours, it’s normal fatigue. Persistent declines = overtraining.

Q2: Can sprint speed return after overtraining?

Yes — with deloading and recovery. Research shows neuromuscular function can normalize within 2–6 weeks depending on severity.

Q3: How much volume is too much?

When performance metrics trend down for more than 10 days despite consistent effort, reduce total load by 30–50%.

Q4: What metrics should coaches track weekly?

Flying 10m time, RSI, resting HR, HRV, and subjective wellness. Trends tell the truth.

Q5: Why does rest improve speed?

Rest restores neural drive and tendon stiffness, both critical for explosive power.

Most athletes never truly train max velocity. Learn how to get faster by improving top-end sprint speed with science-backed methods.

Learn how to get faster with proven acceleration training methods. Improve first-step quickness, horizontal force, and sprint mechanics.

The Speed Plateau Series: How to Break Through and Get Faster

You can get stronger for months and still stay the same speed. Squat up, deadlift up, vertical up, but the 40 does not move. That plateau is common in sprint based sports because sprinting is not a test of how much force you can produce. Sprinting is a test of how much force you can apply in extremely short ground contact times, in the right direction, without leaking it through mechanics or fatigue.

Train with confidence. Know exactly what to work on and why it matters

Access free tools & calculators built to help coaches and athletes train smarter.