Unlock the Secret Under Your Feet

Speed isn’t just strength — it’s bounce. Discover the hidden spring that makes the fastest athletes look effortless. If you’ve

If a sprint race lasts less than a minute, why do so many programs dedicate months to “building work capacity”?

For decades, coaches have leaned heavily on the general preparation period (GPP) — long runs, circuits, and heavy conditioning — to build the athlete’s “engine” before ever touching maximal speed work. The idea is simple: more work capacity equals better resilience, fewer injuries, and readiness for the demands of sprinting.

But here’s the paradox: every hour spent building generic fitness is an hour not spent developing the speed qualities that actually win races. In some cases, the very “capacity” work prescribed may be teaching sprinters to move slower.

How much capacity do sprinters really need — and when does it start costing speed?

In sprint training, this maps onto GPP vs SPP:

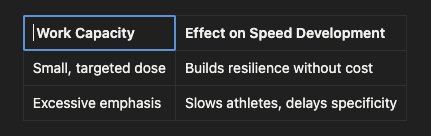

The issue isn’t whether work capacity is good or bad — it’s whether more is always better.

The Goal of Sprint Training: Is More Always Better?

At its core, sprinting is about maximal velocity and speed endurance. The stopwatch, not the work log, decides success.

A 100m sprinter races for ~10 seconds. A 400m sprinter is done in under a minute. Contrast that with marathon training — where capacity rules.

If the race demands are so short, should sprinters devote months to work capacity? Or should they double down on the qualities that win races — explosive force, technical efficiency, and neuromuscular speed?

This is where the debate begins.

Why do so many programs still front-load capacity?

In truth, work capacity does serve a role, particularly for novices and athletes lacking a training base. But for well-trained or multi-sport athletes, the payoff is far smaller.

Here’s the problem: capacity comes at a cost.

As Verkhoshansky’s principle of dynamic correspondence reminds us: training should match the direction, speed, and force demands of the sport [Verkhoshansky & Siff, 2009].

If it doesn’t — you may be moving away from performance, not toward it.

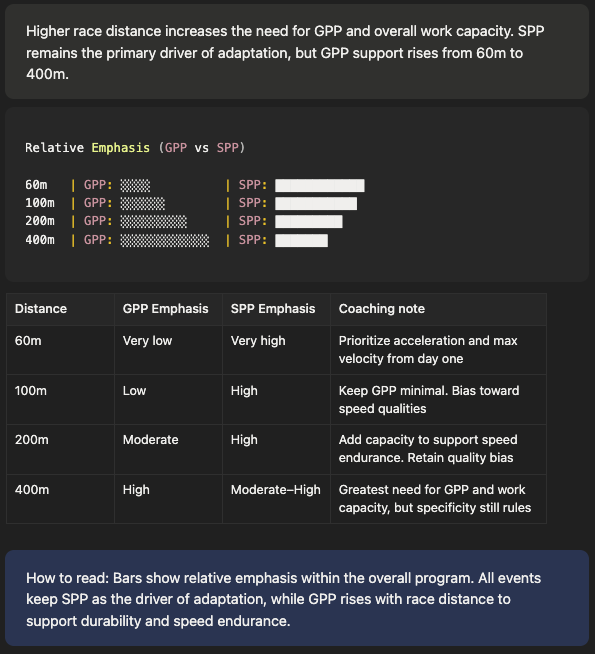

Let’s examine by race distance:

100m Sprinters (10–11 seconds)

200m Sprinters (20–23 seconds)

400m Sprinters (45–50 seconds)

Practical Coaching Guidelines: Striking the Right Balance

How can coaches avoid overbuilding capacity?

So, what’s the goal of training? To make athletes faster — not just fitter.

For sprint coaches, the challenge is resisting the urge to “do more” when sometimes, doing less but better wins the race.

Speed isn’t just strength — it’s bounce. Discover the hidden spring that makes the fastest athletes look effortless. If you’ve

Track what actually matters. Learn the 10 sprint performance metrics every sprinter should monitor, why they matter, and how to measure them accurately.

Learn the physics, biomechanics, and coaching principles behind negative steps and negative foot speed in elite sprinting. Includes research, drills, visuals, and training methods.